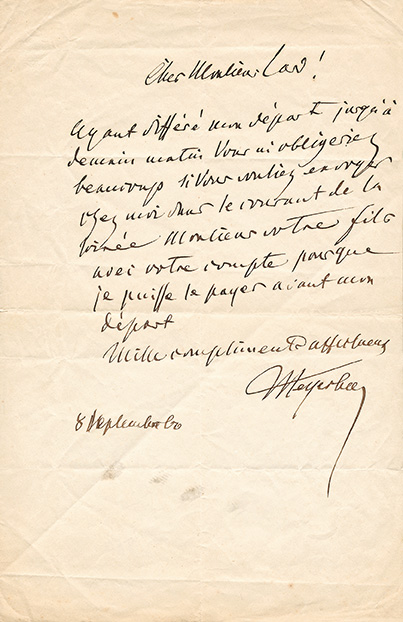

Biographical Sketches

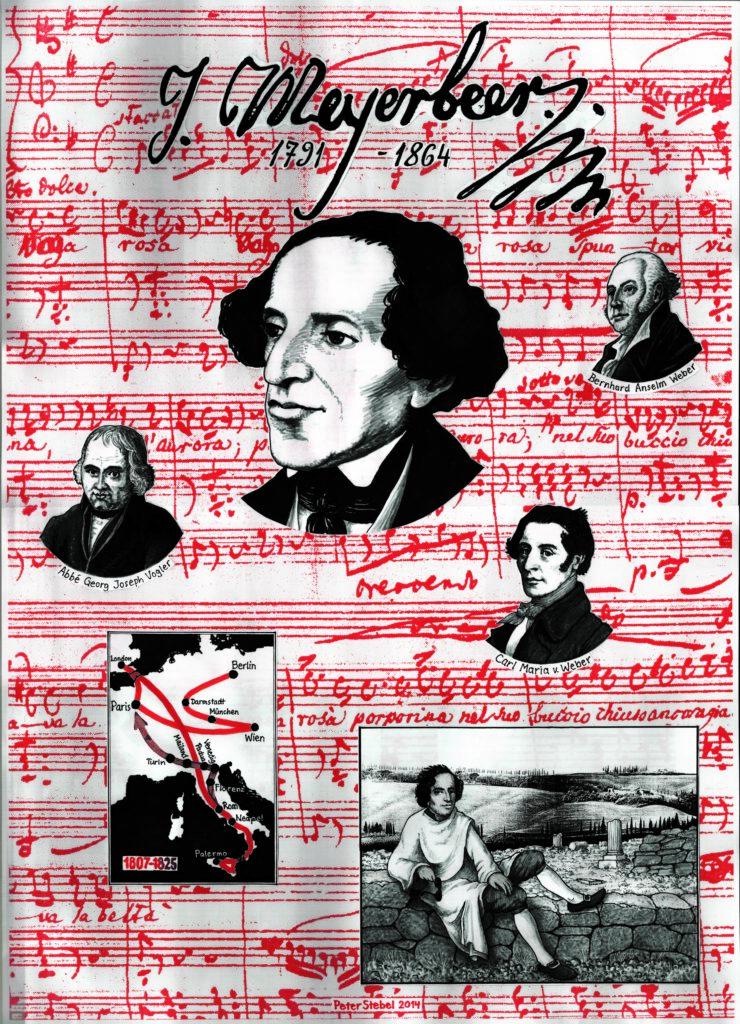

September 5, 1791

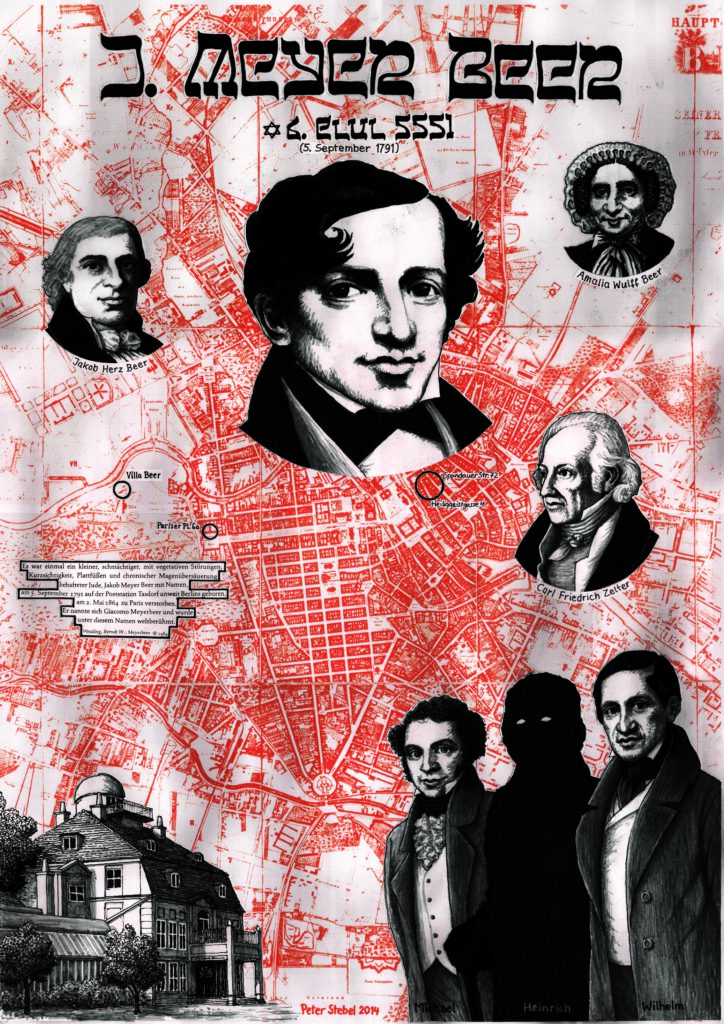

Meyer Beer was born on 5 September 1791 at the gates of the Prussian capital in Tasdorf/Vogelsdorf – today’s Rüdersdorf near Berlin. A pure coincidence, because the actual destination of the journey, Frankfurt an der Oder, is not reached. Meyer’s father Jacob Herz Beer (1769-1825) came from there and married Amalie Meyer Wulff (1767-1854) in Berlin on 4 September 1788. Traditionally, the birth was planned at the home of the parents-in-law in Frankfurt, where everything was already prepared for the birth of the first child. At the post station in Vogelsdorf, where the horses of the carriage were also changed, the journey to Frankfurt came to an abrupt end and Amalie gave birth to a son, allegedly in a covered wagon. Meyer’s father, Herz Beer, was a banker and successful entrepreneur of sugar refineries with branches in Berlin, Italy and at times in Hamburg. Amalie Beer was a daughter of Liepmann Meyer Wulff (1745-1812) and ran a highly respected salon known far beyond the borders of Berlin. Her philanthropy is legendary. Jacob Herz Beer is one of the founders of the Luisenstift and the Königstädtisches Theater. Both families belong to the Reform wing of the Jewish community. Jewish Enlightenment thinkers such as David Friedländer and Aaron Wolfssohn frequented the family home. Meyerbeer had three younger brothers: Heinrich Beer (1794-1842), Wilhelm Beer (1797-1850) and Michael Beer (1800-1833). Wilhelm is an entrepreneur, astronomer and politically active; Michael is a writer and dramatist, while Heinrich more or less shines as an eccentric and non-conformist.

All quotations appear in italics and are, of course, substantiated

1798

Begins piano lessons with the Bohemian-born virtuoso and composer Franz Seraphinus Lauska (1764-1825), who also has the royal princesses and princes under his wing. Lauska later also taught Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. The latter belongs to the four-leaf clover of Meyerbeer’s mortal enemies.

1800

Berlin has 170000 inhabitants. The Jewish share of the population is about 2 percent. The Beer family belongs to the very thin upper class, who achieved great wealth. Most Jews live in precarious conditions and are on the very fringes of society. There are no designated ghettos in Berlin. Liepmann Meyer Wulff gained his fortune as a supplier to the army, he was a tenant of the Prussian lottery, a banker and a member of the council of elders of the Jewish community. Wulff went down in the history books as the Croesus of Berlin.

October 14, 1801

Meyerbeer makes his debut as a pianist in Berlin with Mozart’s Piano Concerto in D minor, KV 466. He is the first Jew to be perceived in public as a virtuoso. He has great success in public concerts and accompanies his teacher Lauska on concert tours. He performs the Mozart concerto several times. KV 466 is still one of the most popular concertos. Mozart is a musical ideal for Meyerbeer. One of his favorite compositions from Mozart’s pen: the divine Ave verum, KV 618.

1803

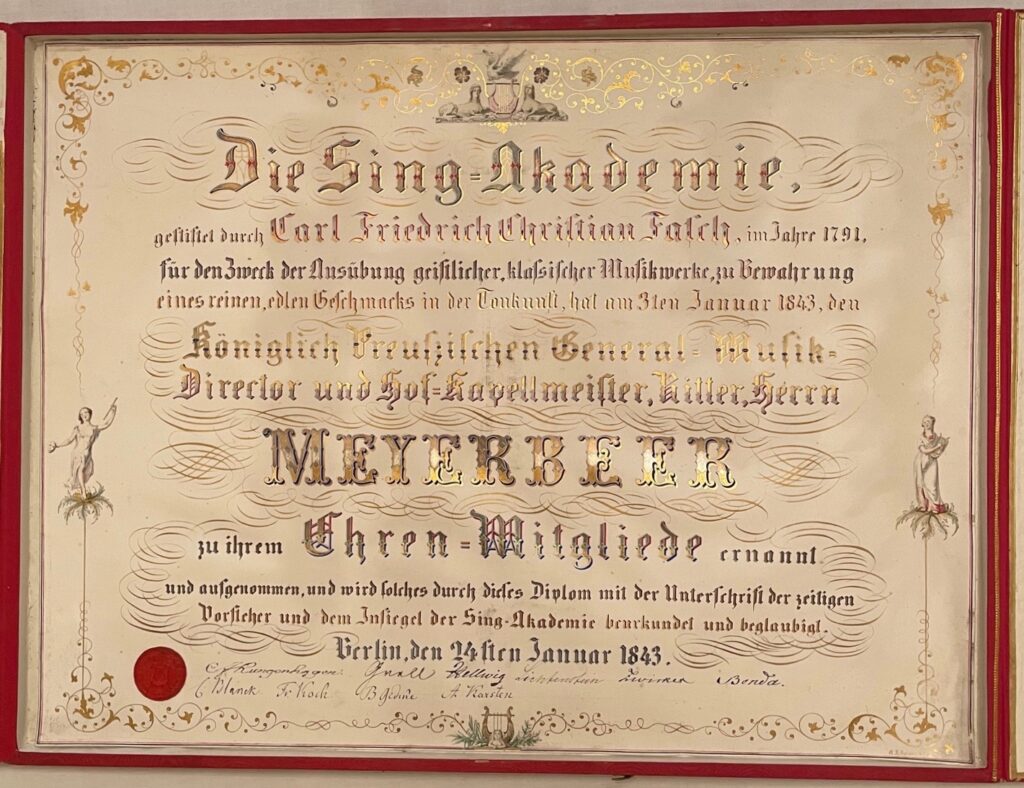

Meyerbeer joins the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin and participates in numerous alto concerts until his voice breaks. These include motets by Johann Sebastian Bach and Georg Friedrich Händel’s oratorio Das Alexanderfest. Meyerbeer later found his own way to Bach. He was particularly fond of the cantata BWV 106, known as Actus tragicus: Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit. The civic choral society founded in 1791 by Carl Friedrich Christian Fasch (1736-1800) is especially famous for mixed a cappella compositions that are in line with the trend of the time. Meyerbeer receives composition lessons from Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758-1832), who takes over the direction of the choir after Fasch’s death. Zelter probably does not succeed in really satisfying his student’s immense thirst for knowledge. In a letter to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Zelter refers to Meyerbeer as one of his disciples. For Amalie Beer it is clear in retrospect: it is a pity that he spent 2 years so uselessly with Zelter. These 2 years are to be regarded as lost.

1805 at the latest

Meyerbeer is taught German, history, geography, mathematics, philosophy, Italian and French by private tutors, a comprehensive humanistic-scientific education. In addition to his native German, he has a perfect command of spoken and spoken Italian and French, a profound knowledge of Latin and probably ancient Greek. His educator and confidant Aaron Wolfssohn (1756-1835), a radical enlightener, instructs him in the basics of the Hebrew language and provides moral support.

1807

Begins studying and composing under the Royal Kapellmeister Bernhard Anselm Weber (1764-1821). Weber is an outstanding conductor of Christoph Willibald Gluck’s operas, and Berlin is known for excellent performances of an Armide, an Orpheus, and both Iphigenias. The Berlin public adored Gluck. Frederick William IV, Meyerbeer’s later employer, even outed himself as a Gluck addict. Meyerbeer learns a lot from Weber, he follows the rehearsals and performances and knows the scores inside out. Meyerbeer has a phenomenal memory, nothing is forgotten, one way or another. Gluck, along with Mozart, is a great role model for him, a musical ideal. Both find their way to Paris, where they have their great successes.

April 1, 1810

Meyerbeer leaves Berlin and goes to Darmstadt to attend the musical school of Georg Joseph Vogler (1749-1814). His departure from Berlin inspires him; it is a liberation. He leaves the Prussian capital, which is far from being a metropolis. Meyerbeer wants to discover the world. He is ambitious, thirsty for knowledge and full of drive. He knows what he can do and what he still wants to learn. Before he turns his back on Berlin for many years, he creates a family album for himself, containing entries from his family and his circle of friends and acquaintances in Berlin. His teacher Weber writes: Fear God! Love your neighbor! Do right, shun no one! Be mighty in fortune and misfortune. Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752-1814), the former Royal Court Kapellmeister under Frederick II, followed the musical development of the young Meyerbeer with great attention. Reichardt, who was dismissed as Royal Kapellmeister by Frederick William III in 1794 after 19 years of service because of his democratic convictions, was a welcome guest in the Beer house. A guest who is not a Jew-hater. The family has a sense for true or feigned friendliness. Reichardt writes in Meyer’s family book: „What delights man, with which he makes others happy, nature and skill gave you, now also learn to accomplish what pure will and constant zeal alone can accomplish, and in making many happy you will then be highly delighted.

In Darmstadt, Meyerbeer befriended Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) and Gottfried Weber (1779-1839). Weber is a lawyer, composer and music theorist and also a student of Georg Joseph Vogler (1749-1814). All are members of the Harmonischer Verein founded by Weber. Founding purpose: literary lobbying. Meyerbeer writes, among other things, a review on the occasion of the premiere of Weber’s Silvana on September 16, 1810 in Frankfurt am Main. His pseudonym is Julius Billig. All members of the society conceal their true identity. Simon Knaster, Melos or Fräulerin Seraphine von Blocksberg speak for themselves. Meyerbeer’s covenant name: Philodikaios.

Meyerbeer’s wallet is always well filled, and he is generous. The Weber-Meyerbeer-von Weber trio went on excursions in the surrounding area and enjoyed themselves. They also visited nearby Frankfurt, where they made use of certain services in public houses. They are just like that, the young people! – Yes, yes! muses the Marschallin in Strauss’s Rosenkavalier. Meyerbeer confides a rather piquant experience to his diary, which we will not quote here for reasons of discretion and the protection of minors. We ask for your understanding.

March 17, 1811

Bernhard Anselm Weber performs Meyerbeer’s 98th Psalm for choir and orchestra for the first time in a charity concert for the benefit of the Friedrichstift, a social institution for poor soldiers‘ children. Sing to the Lord a new song, for he does wonders. He creates salvation with his right hand and with his holy arm. The autograph of this composition is in Meyerbeer’s lost estate. At least reviews have survived. The critic Johann Karl Friedrich Rellstab (1759-1813) writes in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung :

The conclusion of the first part was the 98th Psalm after Moses Mendelsohn’s translation, composed by the talented young Meyer Beer, who is now striving to develop himself even more with Abbot Vogler. Even if frequent traces of youth cannot be denied in the work, just as many good and well-behaved passages testify to the eighth musical spirit, which under good direction still promises many a beautiful pleasure.

May 8, 1811

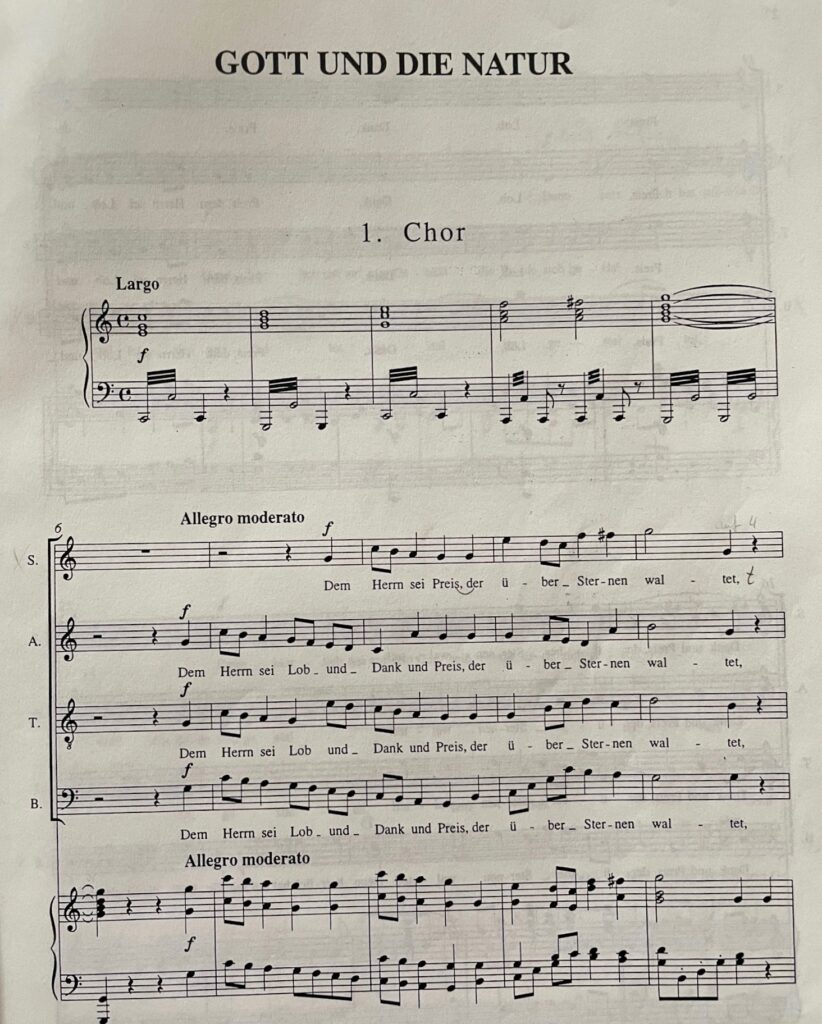

Successful premiere of the oratorio, the lyrical rhapsody Gott und die Natur in Berlin. Bernhard Anselm Weber conducts. The libretto is written by Aloys Wilhelm Schreiber (1761-1841). His Lehrbuch der Aesthetik (1809) was quite famous at the time. Meyerbeer does not travel to Berlin for the performance. His relationship with Berlin is and will remain difficult. Johann Karl Friedrich Rellstab reviews the work on May 14, 1811, and pays respect and tribute to it:

In this rhapsody, the flowers, the elements, are personified and introduced in song. The young composer, who is now studying with Vogler, has appeared in this piece very much to his advantage. (…) Among the choruses, the first is probably the weakest and the last the best. (…) In the other choruses, there was much work and moving basses in Hass’s manner, power in Handel’s style, painting and effect according to Haydn’s pattern card. The style was on the whole well and evenly kept, not in strict church style, but in serious chamber style.

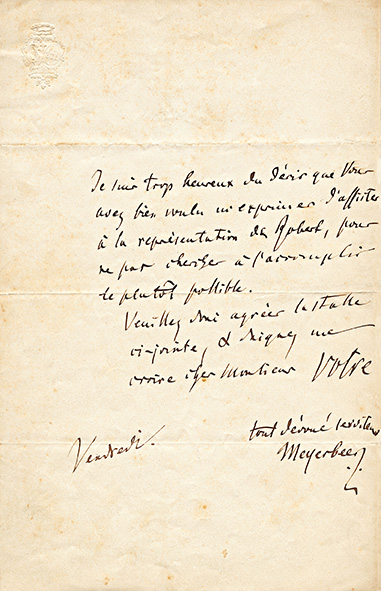

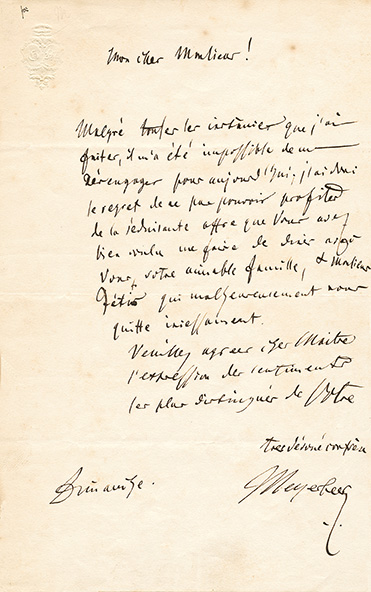

May 22, 1811

In a letter from Meyerbeer to Gottfried Weber, Meyerbeer refers to Rellstab and his criticism of Gott und die Natur. He counts Rellstab as one of his enemies, since he had passed such biting judgment on me a few months earlier. This concerned the 98th Psalm. But now he feels an inner satisfaction. What humiliation for this wretch to have to praise me so almost against his will! Apart from that, Meyerbeer never publicly comments on reviews of his compositions, just as he never publicly utters a bad word about his composing colleagues and their works. The diaries are all the more unambiguous.

In Würzburg, where Meyerbeer is completing his opera Jephta’s Vow, he begins to keep a diary. The first entry:

Already in the beginning of January it was determined that Vogler & I should go to Munich. Therefore, I postponed the beginning of the diary of 1812 from day to day, because I wanted to start it with the journey. But this journey was postponed for a thousand different reasons (sic) until March 8 (Sunday), where we then finally left Darmstadt & arrived the 9th evening in Würzburg. Unfortunately I had to stay there for 5 weeks, because Vogler wanted to give 3 organ concerts, which I would have liked to attend. In the course of the 5 weeks, only one organ concert was given & since I must necessarily be in Munich soon, as I want to try to bring a new opera „Jephtas Gelübde“ (which I completed in Würzburg on April 6) to the stage there, I decided to leave Vogler.

April 13, 1812

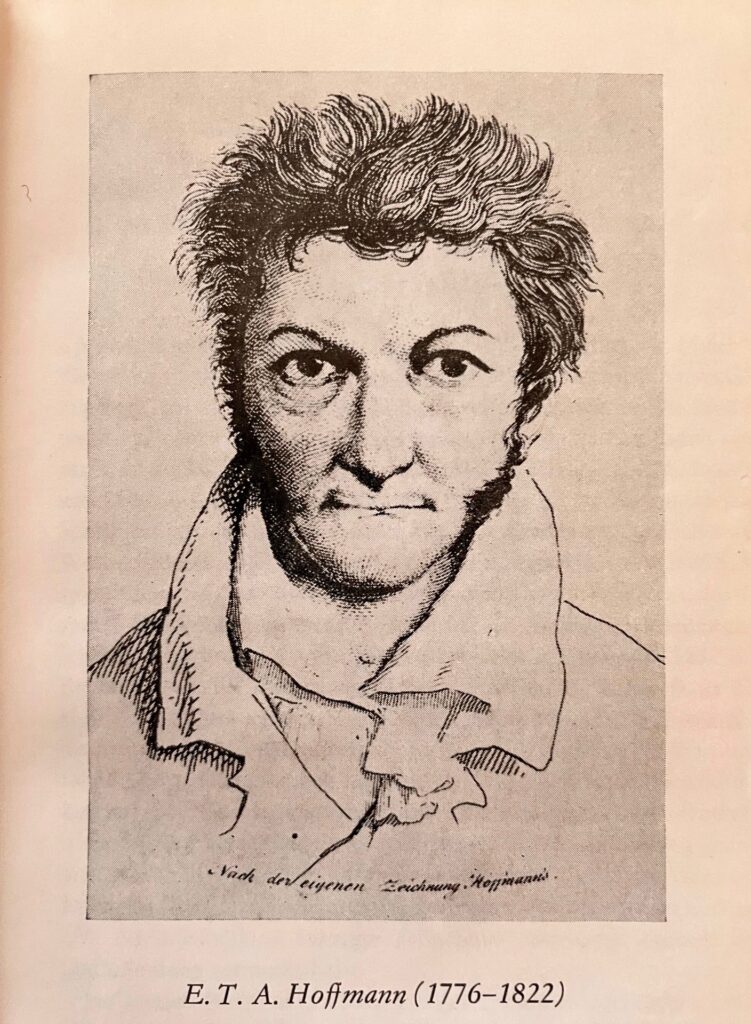

It is a Monday. Meyerbeer is staying in Bamberg. Together with Vogler, he visits the Institute of the Incurably Ill, whose director (a Catholic priest) was an acquaintance of the professor. After the midday meal, they set off on foot, past picturesque landscapes, to nearby Bug, where there is a historic encounter between two top-class geniuses. Meyerbeer records the rendezvous in his diary: „The way there is immensely romantic. There were several guests in Bug, among them the local music director (E. T. A.) Hoffmann, formerly a Prussian war councillor (…). Doctor Feist presented me to him, & since my name, as he said, had been known to him for some time, a lively musical conversation soon ensued. What they so animatingly got into conversation about, only the gods know, if at all. Presumably it was about the mystery of music and the word itself. Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (1776-1822) writes in Die Serapions-Brüder: „Poets and musicians are the most intimately related members of a church: for the mystery of the word and of the sound is one and the same, which has opened up the highest consecration for them.

April 25, 1812

Meyerbeer arrives in Munich, having completed his training with Vogler. Through letters of recommendation, he is introduced to Munich society. If an aspiring virtuoso and composer wants to be successful, there is no way around the salons, where one is virtually passed through. With a lot of luck, a concert of one’s own beckons as a reward. Meyerbeer’s piano playing arouses admiration. He is one of the best pianists of his time.

August 16, 1812

Death of the beloved grandfather Meyer Wulff. In a letter of condolence to his mother, Meyerbeer gives her a solemn promise to always live in the religion in which he died. Meyerbeer is always aware of his Jewish origins, with all the consequences that this entails. Anti-Jewish resentment is omnipresent.

December 23, 1812

World premiere of the opera Jephtas Gelübde with moderate success at the Hof- und Nationaltheater in Munich. Aloys Schreiber writes the libretto.

January 6, 1813

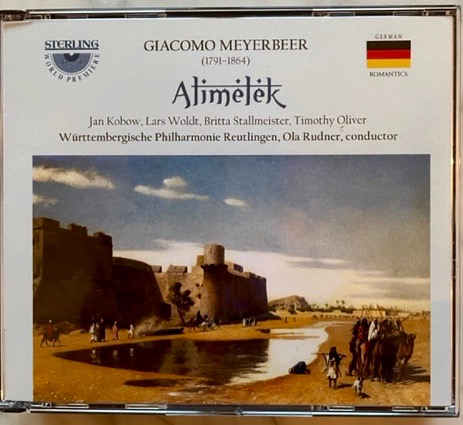

First performance of the comedy with song Wirth und Gast oder Alimelek in Stuttgart. The libretto was written by Johann Gottfried Wohlbrück (1770-1822) based on a story from One Thousand and One Nights.

February 12, 1813

The Grand Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt appoints Meyerbeer court composer. An honorary title.

March 12, 1813

Arrival in Vienna. It is the time of the Congress of Vienna. Encounters with Antonio Salieri, Ignaz Moscheles, Louis Spohr, among others. Meyerbeer shines in the salons as a virtuoso pianist.

January 2, 1814

At the performance of the bombastic Battle Symphony, conducted by the already deaf Beethoven, Meyerbeer participates on the bass drum and probably does not beat in time due to excitement. Beethoven rebuked him. This is still the case today. Discouraged by the weak success of his German operas, Meyerbeer has a creative crisis. He is undecided whether to continue his career as a piano virtuoso or as a composer.

November 30, 1815

Meyerbeer travels to Paris for the first time. The flair of the city overwhelms him.

December 3, 1815

In Dover, Meyerbeer, accompanied by his brother Wilhelm, sets foot on British soil for the first time after a stormy crossing. Already in Paris, he takes English language lessons.

1816

Start of the journey through Italy: Verona, Rome, Naples, Venice, Aquaro, Milan … and Sicily. An educational journey with a lot of culture. Meyerbeer collects folk tunes and writes them down. Rossini’s Tancredi captivates him.

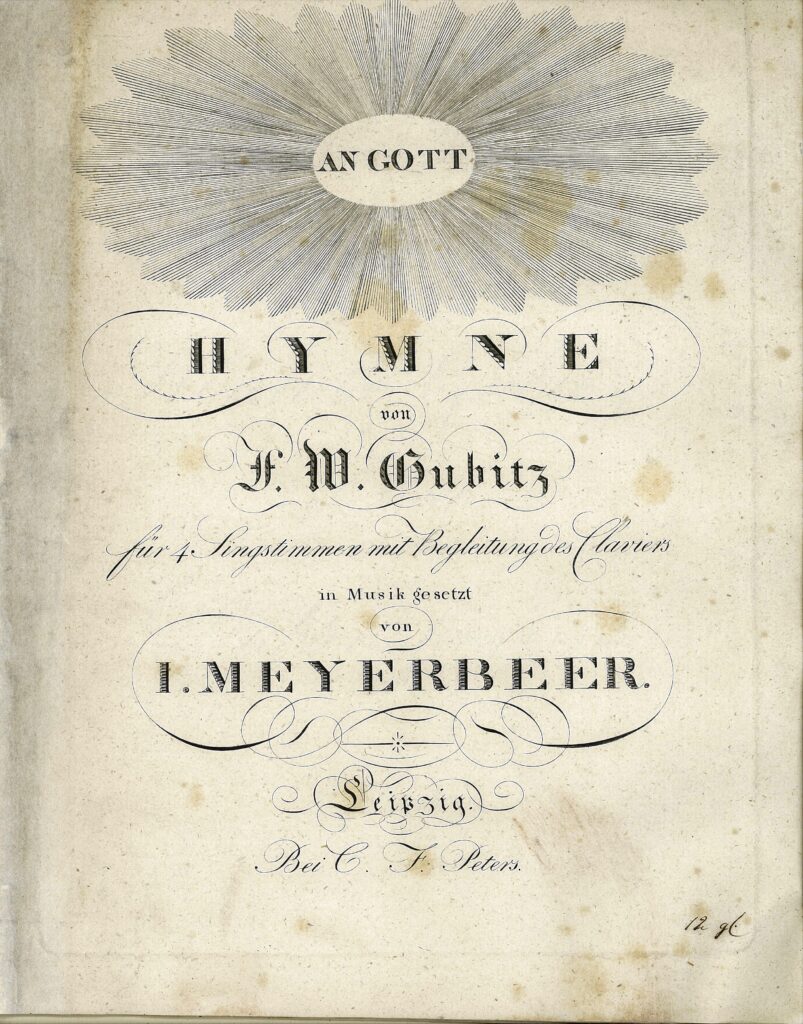

April 1817

The Hymne an Gott (Hymn to God) and the Geistliche Lieder (Spiritual Songs) on texts by Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724-1803) are published by the Peters music publishing house in Leipzig.

July 19, 1817

Inspired by Rossini, Meyerbeer composes his first Italian opera: Romilda e Costanza (melodrama semiserio, 2 acts). The libretto is by Gaetano Rossi (1774-1855). The reviews of the premiere in Padua at the Teatro Nuovo are gratifying for him.

February 3, 1819

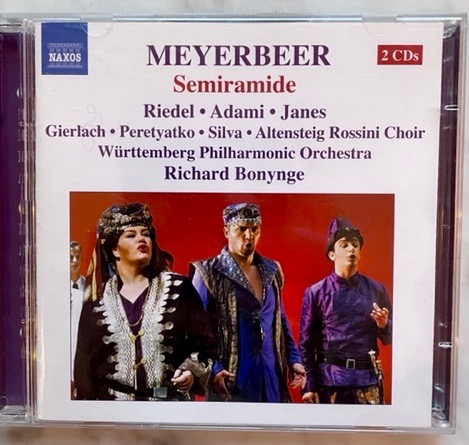

First performance of the opera Semiramide riconosciuta (dramma per musica, 2 acts) at the Teatro Reggio in Turin. The adapted libretto goes back to Pietro Metastasio (1698-1782).

June 26, 1819

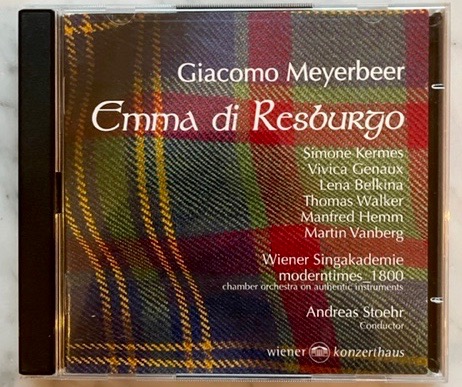

The opera Emma di Resburgo (melodramma eroico 2 acts) is premiered in Venice at the Teatro San Benedetto. The libretto is written by Gaetano Rossi. Emma di Resburgo leaves a strong impression and brings Meyerbeer general recognition in Italy.

October 10, 1819

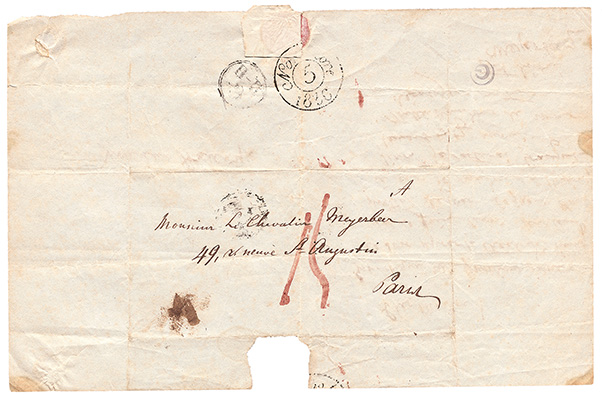

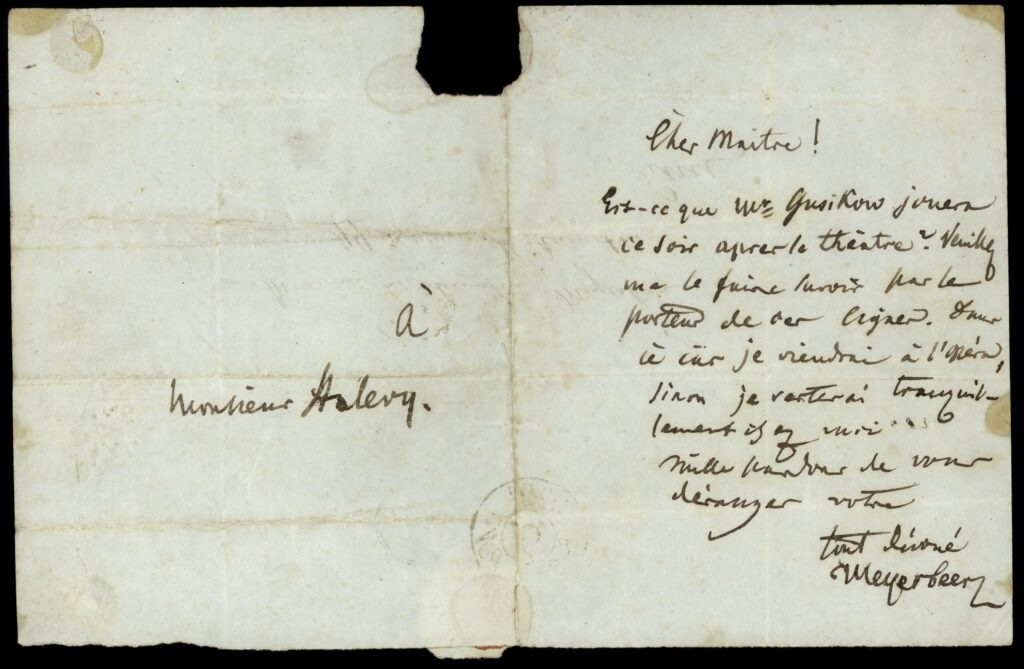

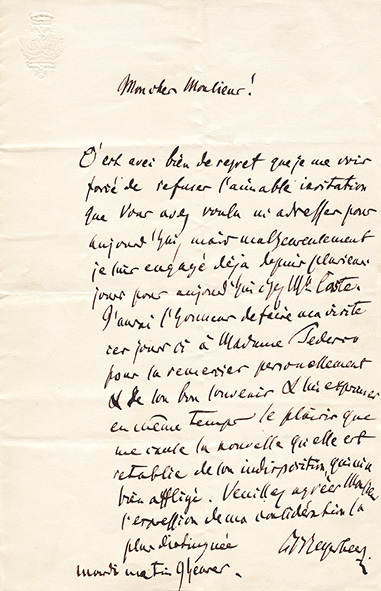

In the first surviving letter in Italian, he signs Giacomo Meyerbeer for the first time. Some letters he writes from Paris in French he signs with Jacques Meyerbeer. The vast majority of his letters he signs with Meyerbeer. Nomen est omen.

February 11, 1820

First performance of Meyerbeer’s Emma di Resburgo in Berlin in German translation as Emma von Roxburgh at the Königliches Theater. The war councillor Johann Christian Carl May takes on the task. Meyerbeer is generally sceptical about translations. The tenor of the review in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung: Meyerbeer conforms smoothly to Italian opera, whose libretti per se have no literary depth, but according to German views should be appropriate to the content.

November 14, 1820

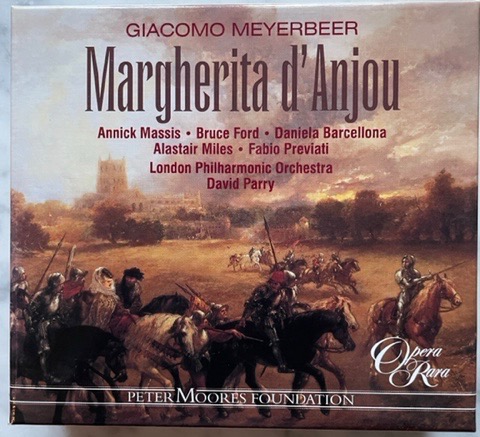

The premiere of Margherita d’Anjou (Opera semiseria, 2 acts) at La Scala in Milan is a brilliant success. The librettist is Felice Romani (1788-1865).

March 12, 1822

First performance of L’Esule di Granata (opera seria, 2 acts) at La Scala, Milan. Felice Romani writes the libretto. The opera is not a resounding success.

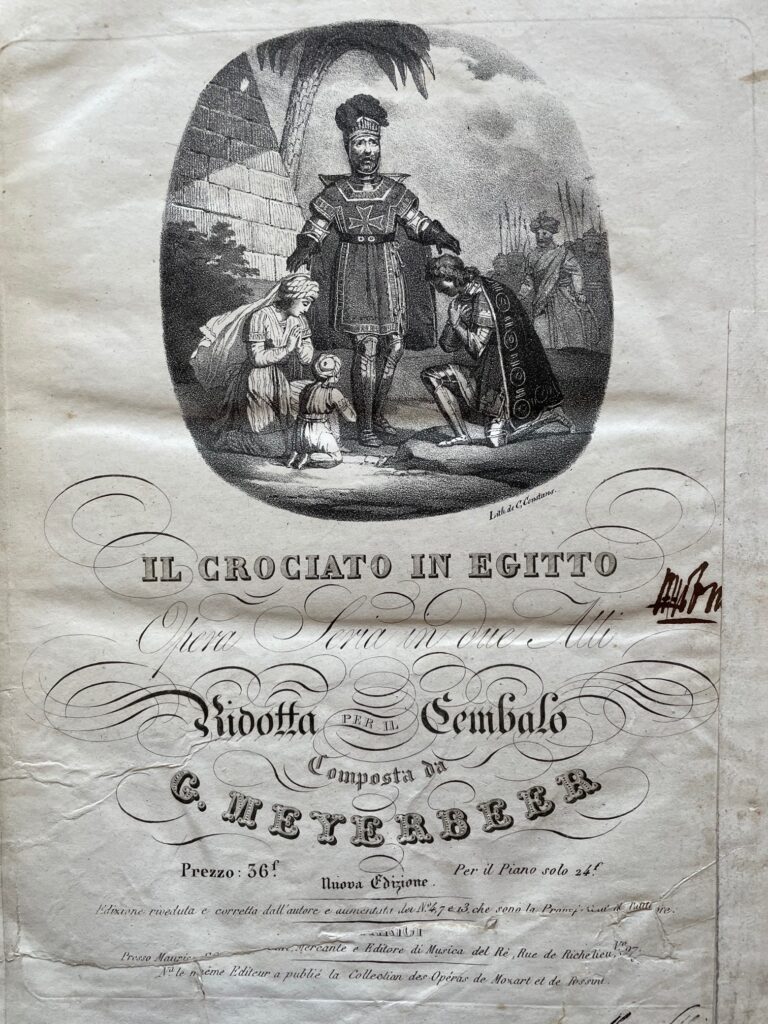

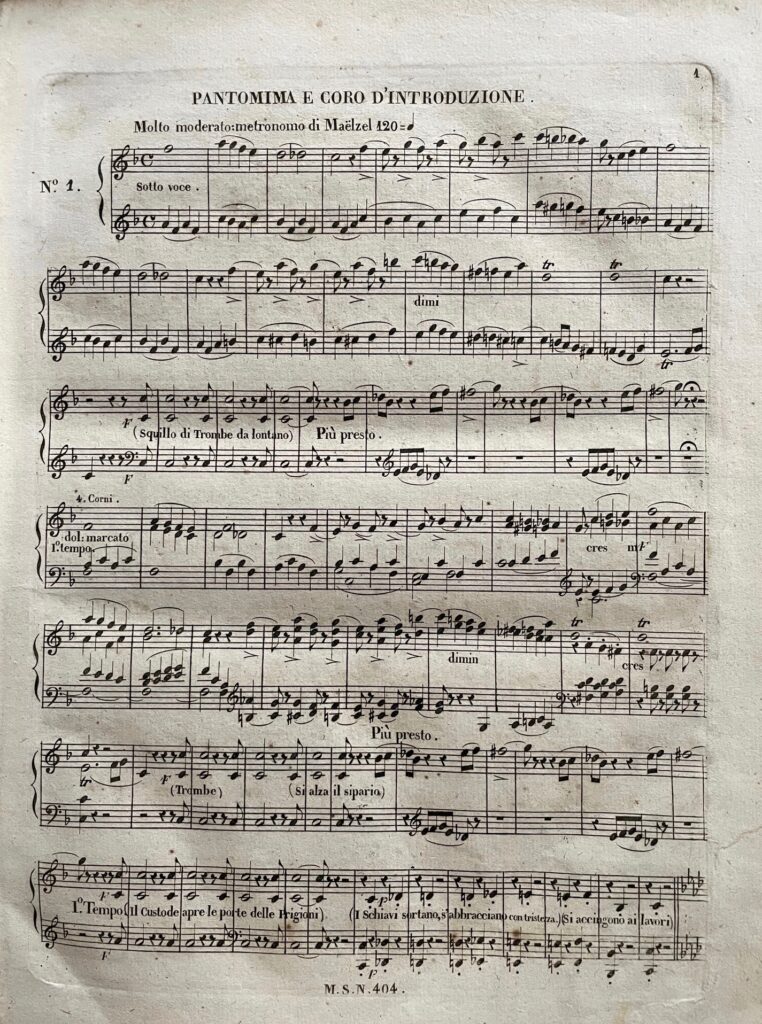

March 7, 1824

The premiere of the last Italian opera Il crociato in Egitto (opera seria, 2 acts) is a sensational success in Venice. Gaetano Rossi writes the libretto again. An unparalleled triumph – from now on Meyerbeer belongs to the top of European opera. The way to Paris, his real goal, is paved.

August 3, 1824

On the occasion of the inauguration of the concert hall in Beer’s Villa in the Tiergarten, Meyerbeer comes to Berlin on a short visit. Last meeting with Carl Maria von Weber.

February 23, 1825

Meyerbeer returns to Paris.

September 25, 1825

First performance of Il Crociato in Egitto at the Théâtre Italien in Paris.

October 27, 1825

Meyerbeer’s father Jacob Herz Beer dies in Berlin. Meyerbeer stays away from the funeral.

May 25, 1826

Meyerbeer marries his cousin Minna Mosson (1804-1886) in Berlin. Why the choice fell on that Minna is not known. The following advertisement appears in the Königliche privilegierte Berlinische Zeitung (Vossische Zeitung): J. Meyerbeer Minna Meyerbeer, née Mosson, hereby honours her relatives and friends with the announcement of her marriage on 25 May. Lea Mendelssohn Bartholdy, who converted to Protestantism with her husband Abraham Mendelssohn in 1822 and brought up their four children as Christians, has her own special view of this marriage, which sheds a telling light on the gulf between converted and non-converted Jews. Lea writes to her cousin Henriette von Arnstein in Vienna, not without a dig at Minna:

Incidentally, the fact that in the extensive Mosson-Beer-Ebers family, not 10 men can be found who can provide the müngen (i.e. dialectal, Yiddish variant of minyan = for a Jewish service, 10 mature men are needed) in good Old Testament terms, testifies to the progress of Christianity into Judaism. Everyone is surprised that this composer does not marry a muse, but a mosson, who is not even a grace, from which the world will conclude that there are no muses and graces in the Mark, although Goethe wrote a title like this.

The marriage between Minna and Giacomo produced three daughters: Blanka (1830-1896), Cäcilie (1837-1931) and Cornelie (1842-1922). Two children die in infancy, Eugénie (16 August – 9 December 1827) and the only son Alfred ((31 October 1828 – 13 April 1829).

January 1, 1827

Begins working with Eugène Scribe (1791-1861).

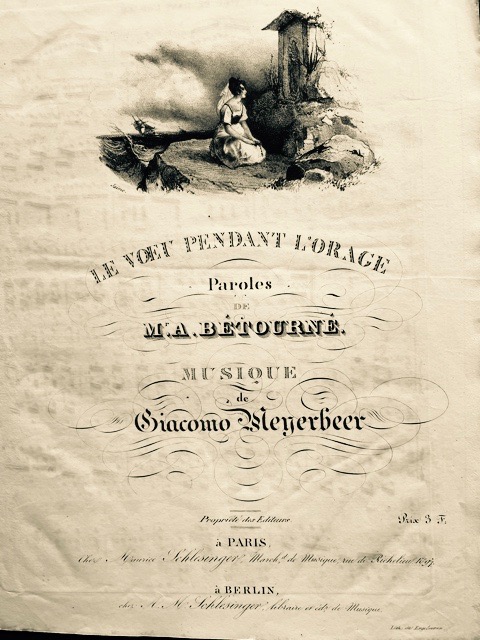

1830

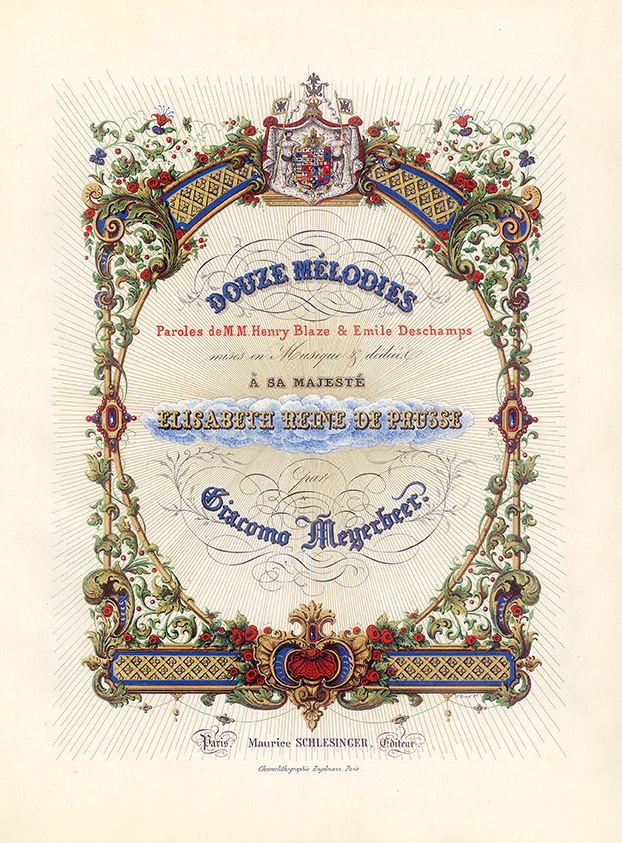

The Gebet während des Sturms (Prayer During the Storm) appears, just one of Meyerbeer’s far more than one hundred songs, romances and mélodies.

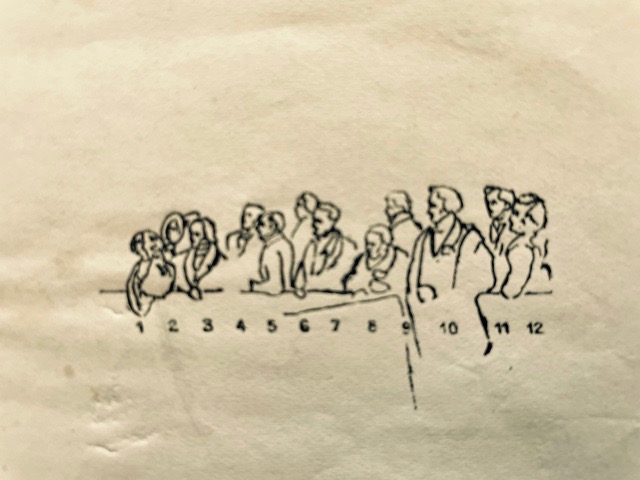

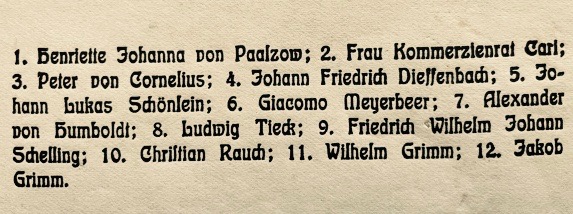

January 15, 1831

Meeting with Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) in Paris, both are bound by a lifelong intimate friendship. Humboldt, his fatherly friend, becomes Meyerbeer’s advocate and mentor. The two cosmopolitans get along splendidly.

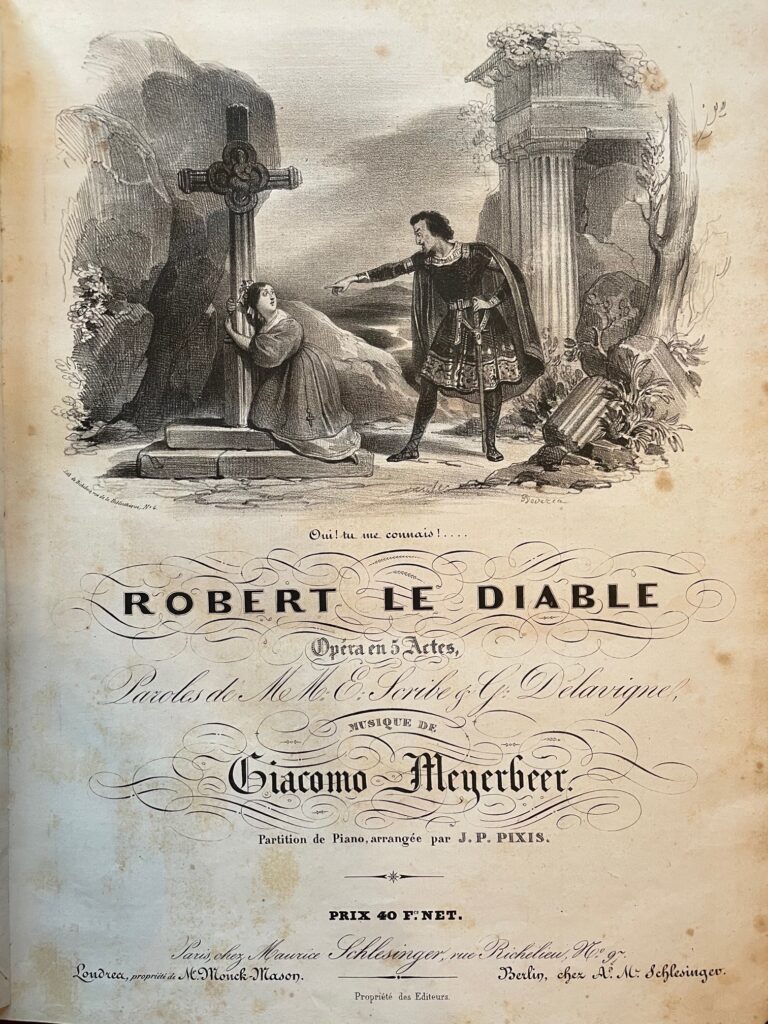

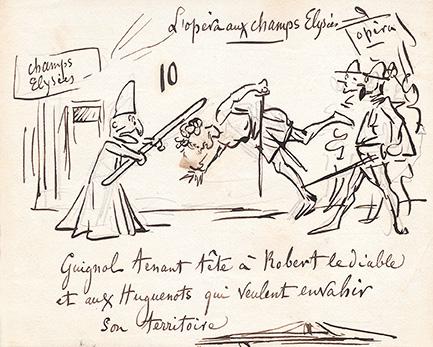

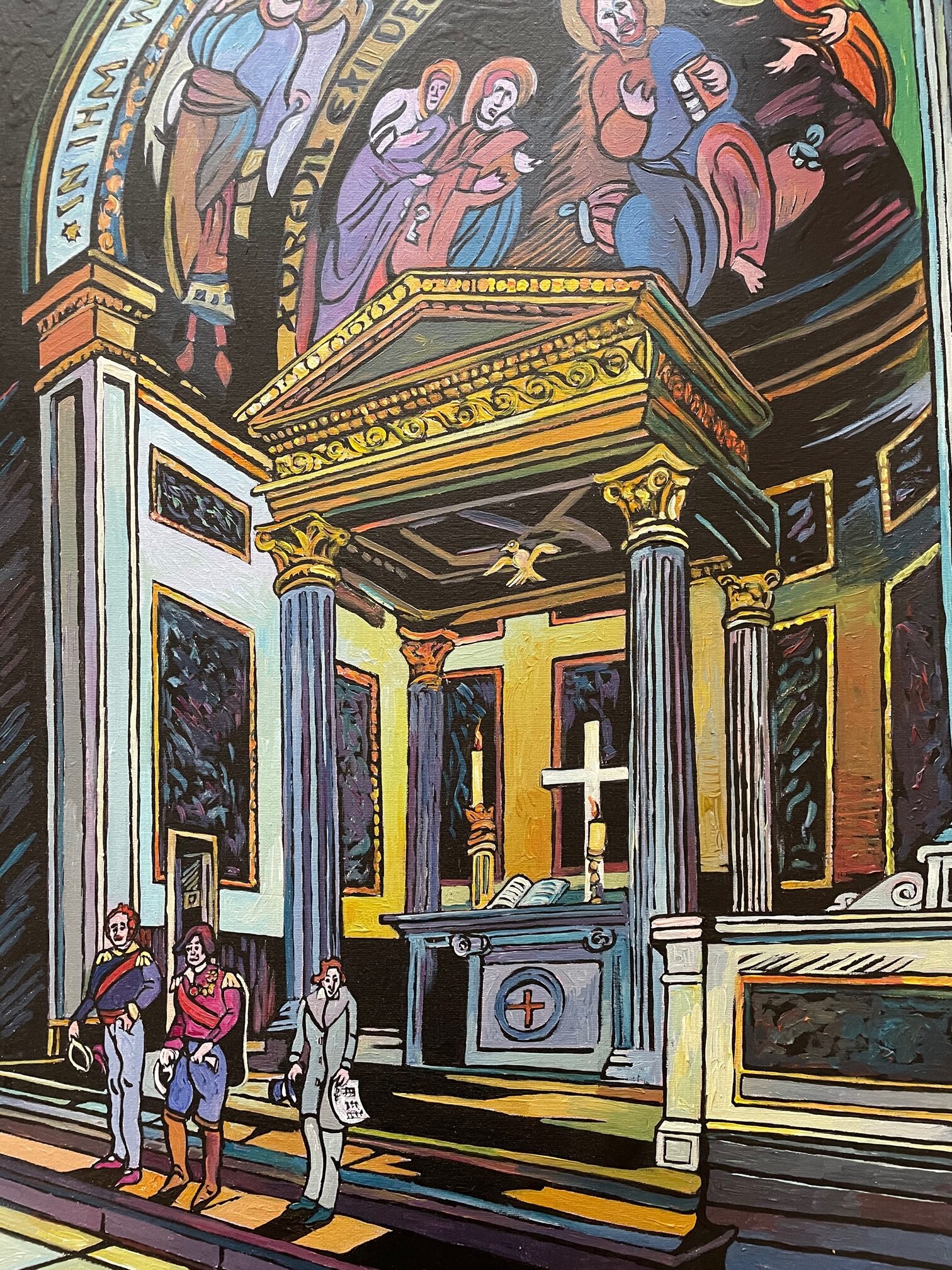

November 21, 1831

The first performance of the Grand Opéra Robert le Diable in Paris is a triumph. Originally, a three-act opéra comique was planned, i.e. with spoken dialogue. The libretto is written by Eugène Scribe and Germain Delavigne (1790-1868). Audiences and critics are thrilled by the opulent sets, the subject matter, the grandiose music and the lighting: gaslight! That is new. One of the highlights is the infamous nuns‘ ballet. In the pale light, the hero is seduced by the sinful souls of the nuns, but the end is bitter as the desirable girls turn into hideous grimaces. Novelty: Robert’s eroticising ballet scene is danced on pointe for the first time! The acclaimed star is the prima ballerina Marie Taglioni (1804-1884), already a legend and myth in her own lifetime. Her father Filippo Taglioni (1777-1871) creates the choreography. The house races.

Alexander von Humboldt is thrilled and sends a letter to his compatriot. Je ne puis me coucher, Monsieur sans avoir parlé de mon admiration sans vous l’exprimer dann la même langue dans laquelle elle a retendi autour de moi pendant toute la durée de cette belle représentation. Vous devez être heureux et je le suis avec vous, car je suis de ceux Wii jouissent de la gloire de leurs amis qui voyent grandir avec cette gloire celle de la patrie commune. Vous avez Ei un beau sujet à traiter, mais qui en d‘autres mains, par des écarts d‘imagination, pouvait conduir à Mal. Je ne connais rien de si dramatique wie Votre musique, et quelle flexibilité d‘un grand talent, quelle variété de caractère de l‘aimable gaieté du „bonheur est dans l‘inconstance“ elle seul embellit nos jours, et aux sublimes et solennels effets du choeur de la caverne „noirs démons, fantômes“ le „qu‘as tu donc entendu“ et le fin terrible du 4me Acte, dont le choeur „arrêtons saisissons ce guerrier téméraire“ est (Salon le jugement des grands connaisseurs) un des plus étonnants morceaux de la musique dramatique.(Translation in english:I cannot go to bed, Sir, without having spoken of my admiration without expressing it to you in the same language in which it was expressed around me throughout this beautiful performance. You must be happy and I am happy with you, for I am one of those who enjoy the glory of their friends and who see the glory of the common country increase with it. You have a beautiful subject to deal with, but which in other hands, by deviations of imagination, could lead to evil. I know nothing so dramatic wie Your music, and what flexibility of a great talent, what variety of character from the amiable gaiety of „happiness is in inconstancy“ it alone embellishes our days, and to the sublime and solemn effects of the chorus of the cave „black demons, fantômes“ the „qu’as tu donc entendu-what did you hear“ and the terrible ending of Act 4, whose chorus „arrêtons saisissons ce guerrier téméraire-let’s arrest this reckless warrior“ is (Salon le jugement des grands connaisseurs) one of the most astonishing pieces of dramatic music.)

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy attends a performance, is piqued by the indecent content and intends to compose only sacred music from then on. In Paris alone, the work was performed around 750 times until 1893.

The ten most performed works at the Paris Opera in the 19th century. All numbers are approximate.

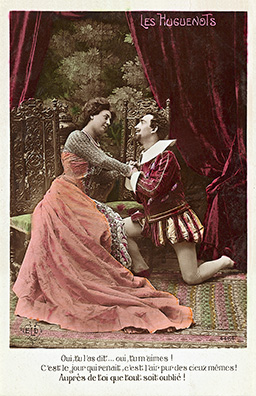

Les Huguenots 950 performances (1836-1900); Faust (Gounod) 860 (1869-1900); Guillaume Tell (Rossini) 800 (1829-1900); Robert le Diable 750 (1831-1893); La Favorite (Donizetti) 680 (1840-1899; La Juive (Halévy) 600 (1835-1893); Le Prophète 530 (1849-1900); La Muette de Portici (Auber) 490 (1828-1892); L’Africaine 460 (1865-1893); Don Juan (Mozart) 300 (1805-1900)

January 19, 1832

Meyerbeer is made a Knight of the Legion of Honour as a member of the Paris Academy of Arts.

June 20, 1832

Berlin premiere of Robert le Diable. The Berlin critic Ludwig Rellstab (1799-1860) dismisses the work and thinks that the composer only ever follows the well-trodden paths of Rossini, Auber, Herold and others. On 11 August, Friedrich Wilhelm III. appoints Meyerbeer as Court Kapellmeister.

May 1, 1833

Meyerbeer is elected a full member of the Prussian Academy of Arts.

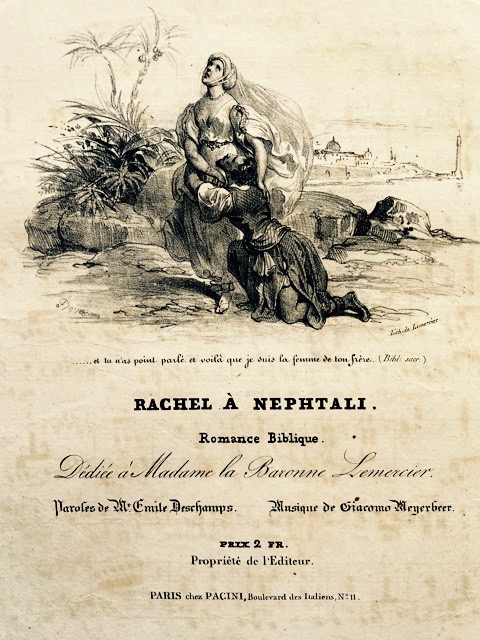

1834

The biblical romance Rachel à Nephtali is published.

February 29, 1836 (Rossini’s birthday)

World-renowned premiere of Huguenots in Paris. The success exceeds all Meyerbeer’s expectations. In the family he is regarded as an outspoken pessimist. Scribe writes the libretto.

April 10, 1837

Leipzig premiere of Huguenots. Robert Schumann’s overall judgement in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik is scathing. Although the self-confessed Meyerbeer hater pays respect to a few numbers (the consecration of the sword and the great duet at the end of Act 4), what is all this compared to the meanness, distortion, unnaturalness, immorality and unmusicality of the whole? Delusional, and praise be to the Lord, we have reached our goal, it can’t get any worse, one would have to turn the stage into a gallows, and the extreme cries of anguish of a talent tormented by time are followed in an instant by the hope that things must get better. Schumann’s criticism serves the Nazis to devalue Meyerbeer’s music.

August 1839

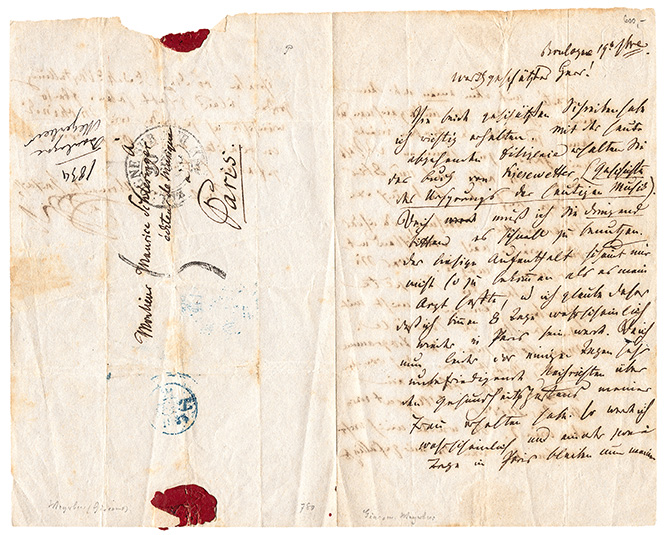

First personal meeting with Richard Wagner in the seaside resort of Boulogne-sur-Mer. Wagner reads the first three acts of Rienzi to Meyerbeer. We would have liked to have been there.

June 7, 1840

Frederick William IV ascends the Prussian throne. The cultural climate changes, so that on 20 May 1842 the Berlin premiere of Hugenotten (Huguenots) can finally take place. Prior to this, the censors intervene. Reason: Meyerbeer’s use of the Luther chorale Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott (a mighty fortress is our God). A higher person, presumably Friedrich Wilhelm III, said that he would not go to an opera where Protestants and Catholics were butting heads, and the Jew was composing the music.

October 15, 1840

Homage to Frederick William IV in front of the Berlin Palace. Of course Meyerbeer is there.

May 31, 1842

Friedrich Wilhelm IV awards Meyerbeer the Order Pour le Mérite of the Peace Class.

June 11, 1842

Giacomo Meyerbeer is appointed Prussian General Music Director. He is responsible for opera and court music, later devoting himself solely to court music. Meyerbeer advocates better pay for musicians and waives his salary.

1843

On 3 January Meyerbeer is appointed honorary member of the Berlin Sing-Akademie.

On 28 February, the Royal Palace in Berlin hosts the premiere of the festival play with living pictures Das Hoffest von Ferrara (The Ferrara Court Feast), for which Meyerbeer composes the music. More than 3000 guests in historical costumes attend.

August 18, 1843

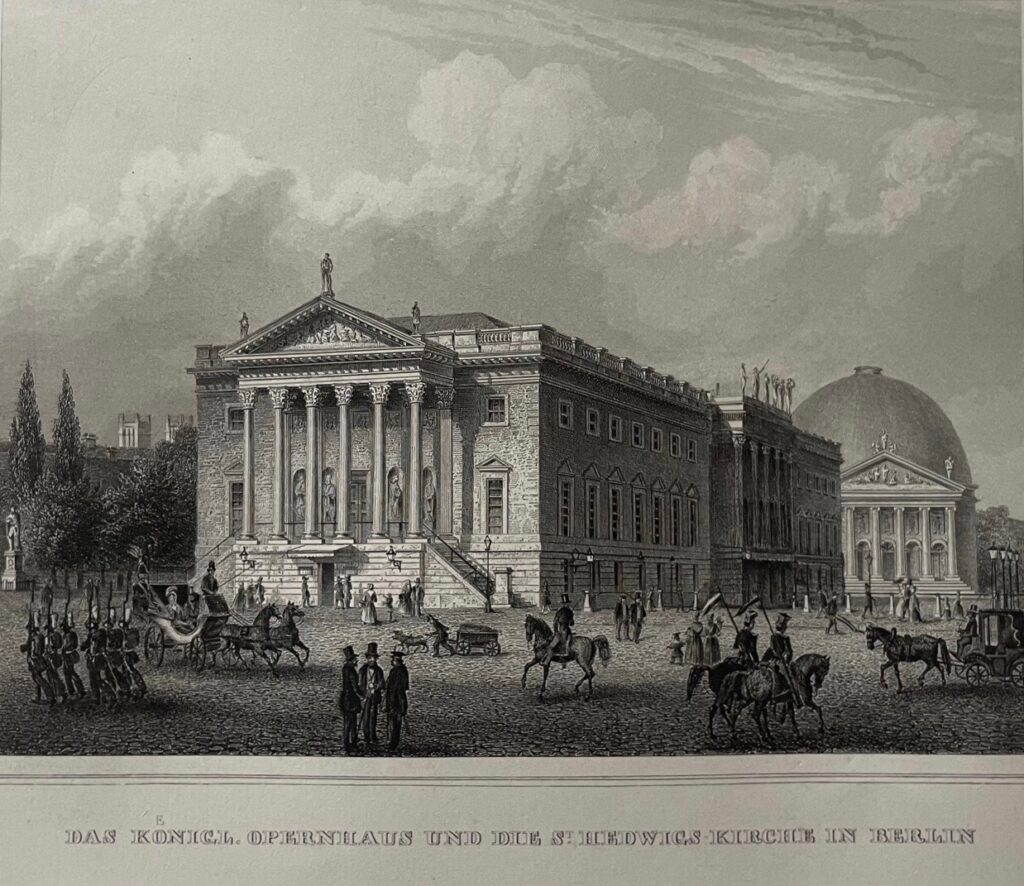

The Royal Opera burns to the ground. Frederick William IV orders immediate reconstruction and commissions Meyerbeer to compose an opera of patriotic content. Result: Das Feldlager in Schlesien (The Camp in Silesia). Scenes from the life of Frederick the Great. For understandable reasons, only a German poet could be considered for it. Meyerbeer, however, had the libretto written incognito by Scribe, which was then translated into German by Ludwig Rellstab. Rellstab was sworn to secrecy and paid a princely sum by Meyerbeer. Rellstab takes an astonishing turn: from being a Meyerbeer detractor to a committed collaborator. In the family correspondence, Rellstab is referred to as the rat.

December 7, 1844

Festive premiere of Das Feldlager in Schlesien (The Camp in Silesia) in the newly built opera house, which now has 1800 seats. Jenny Lind (1820-1887), who had already auditioned for Meyerbeer in Paris, takes over the main role with the second performance, and Berlin is at her feet.

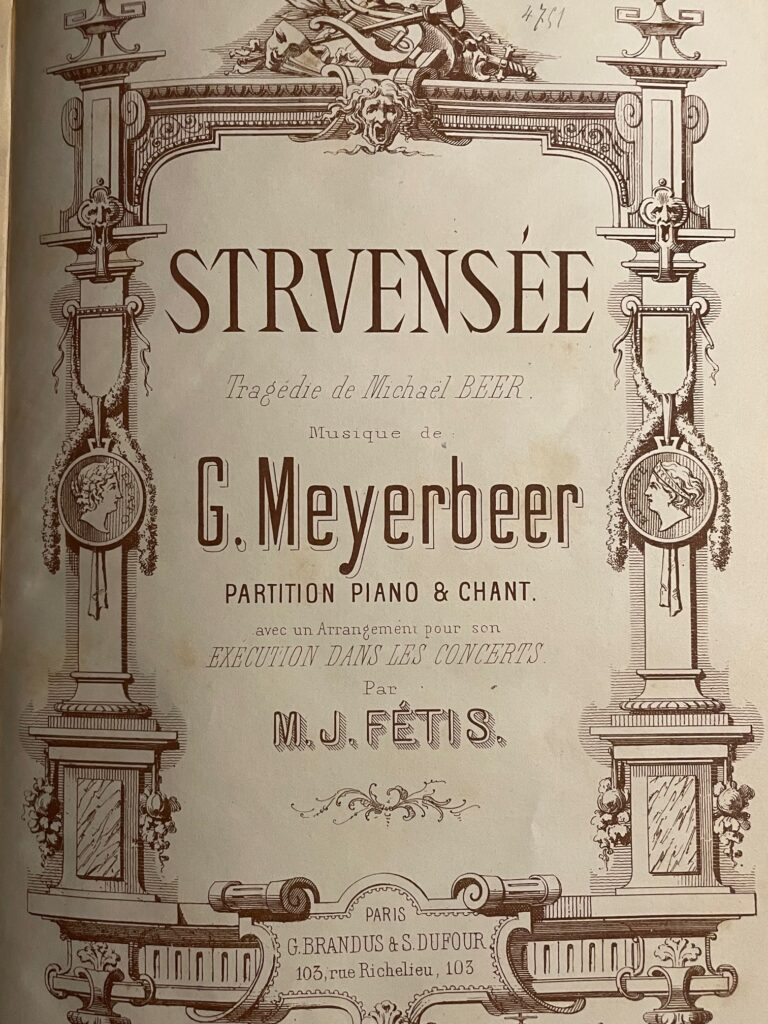

September 19, 1846

World premiere of the play Struensee by Michael Beer with music by Meyerbeer. At the same time, a play of the same name by Heinrich Laube (1806-1884) is to be performed. The Beer family gets its way. Laube defends himself with a sharp pen.

February 18, 1847

Performance of the reworked festival play Das Feldlager in Schlesien (The Camp in Silesia) into the opera Vielka in Vienna. Jenny Lind sings the title role. Vienna is races with excitement.

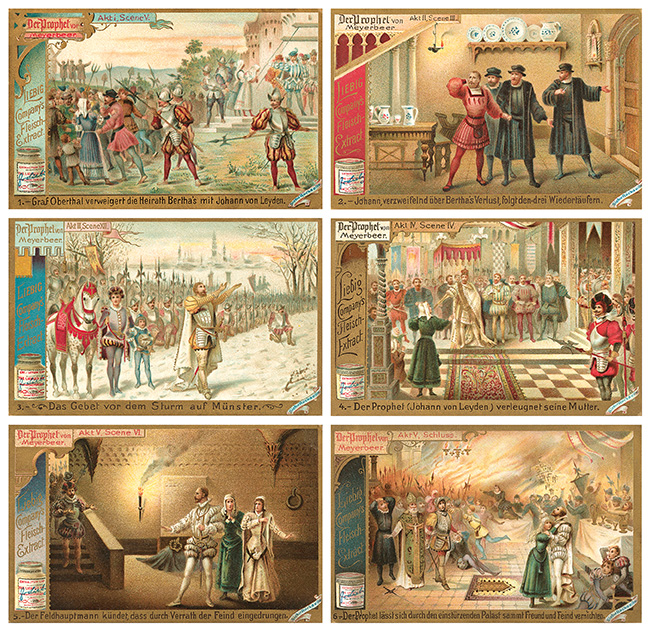

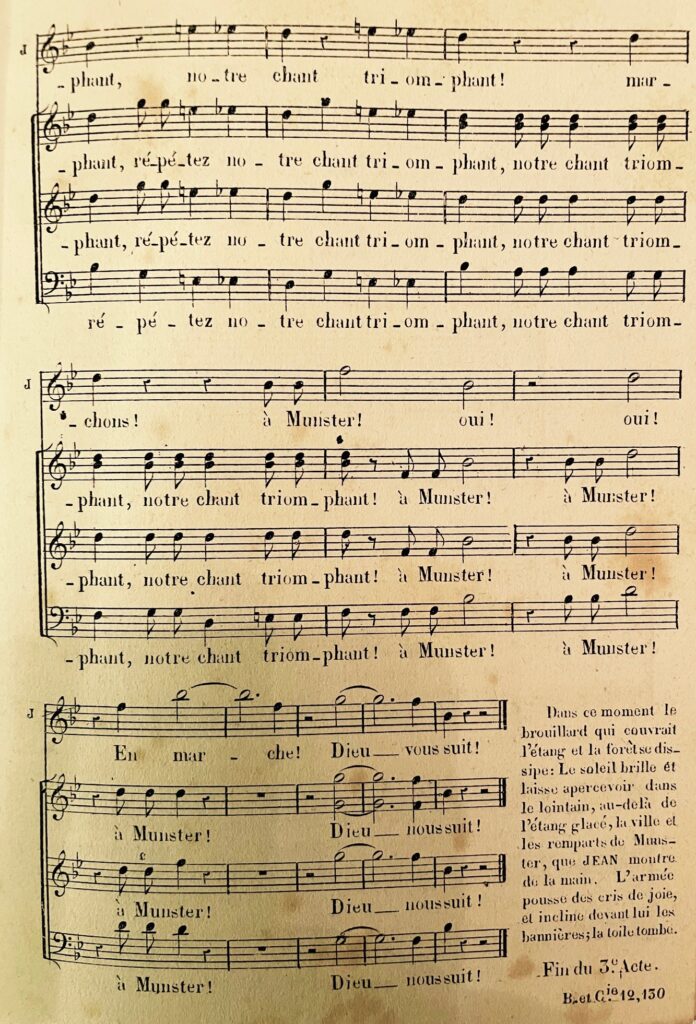

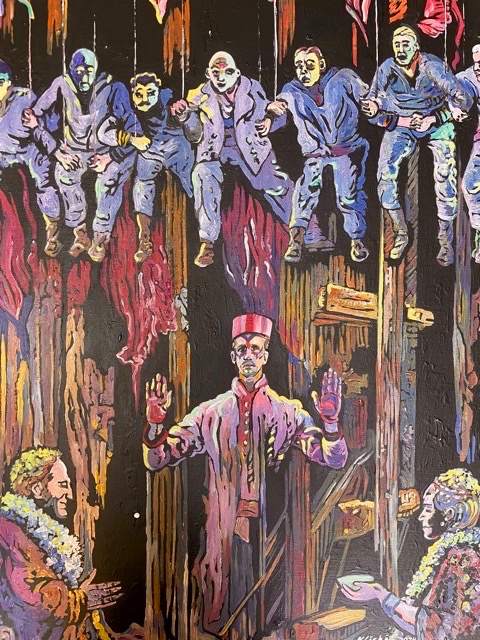

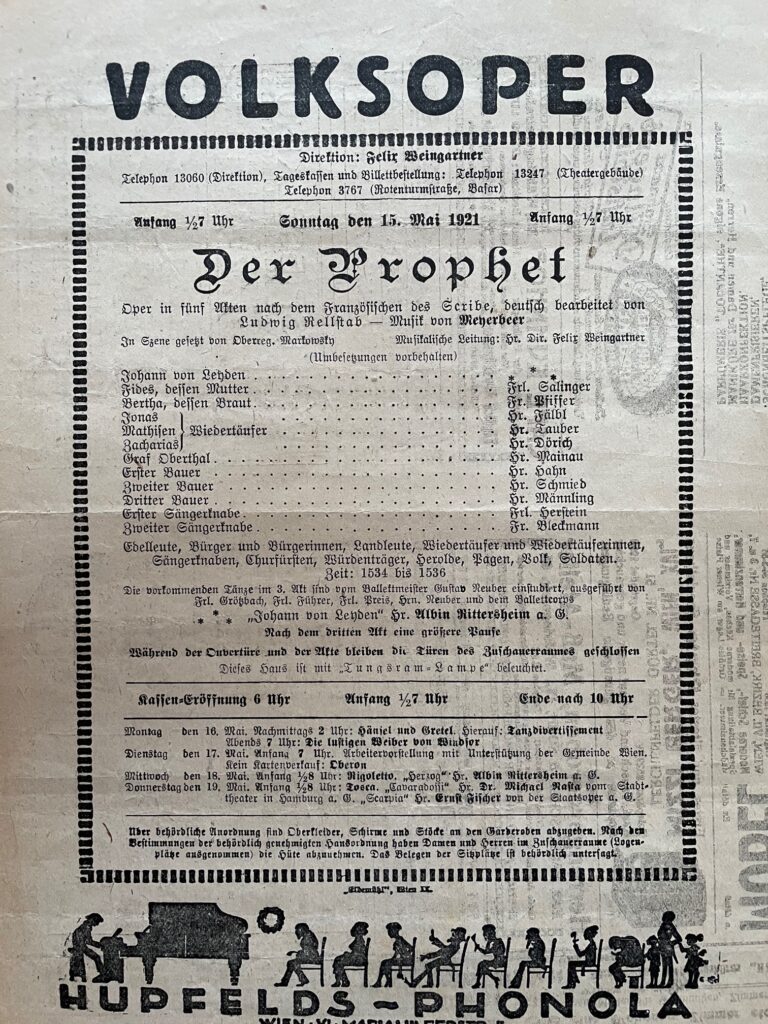

April 16, 1849

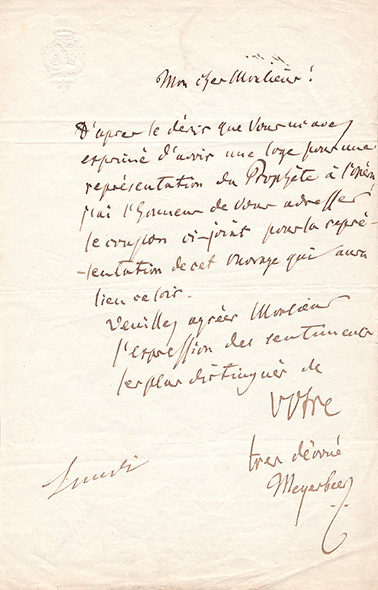

First performance of the Grand Opéra Le Prophète in Paris. The libretto is written by Eugène Scribe. As in Les Huguenots, religious extremism and fanaticism are the focus of the plot. For the first time in the history of opera, electric light is used. The Sonne des Propheten (The Prophet’s Sun) arouses the greatest astonishment. The critical world is divided. Meyerbeer is the most hated composer of the 19th century. Meyerbeer receives from his publisher the highest sum ever paid for an opera score.

April 28, 1850

First performance of The Prophet in Berlin.

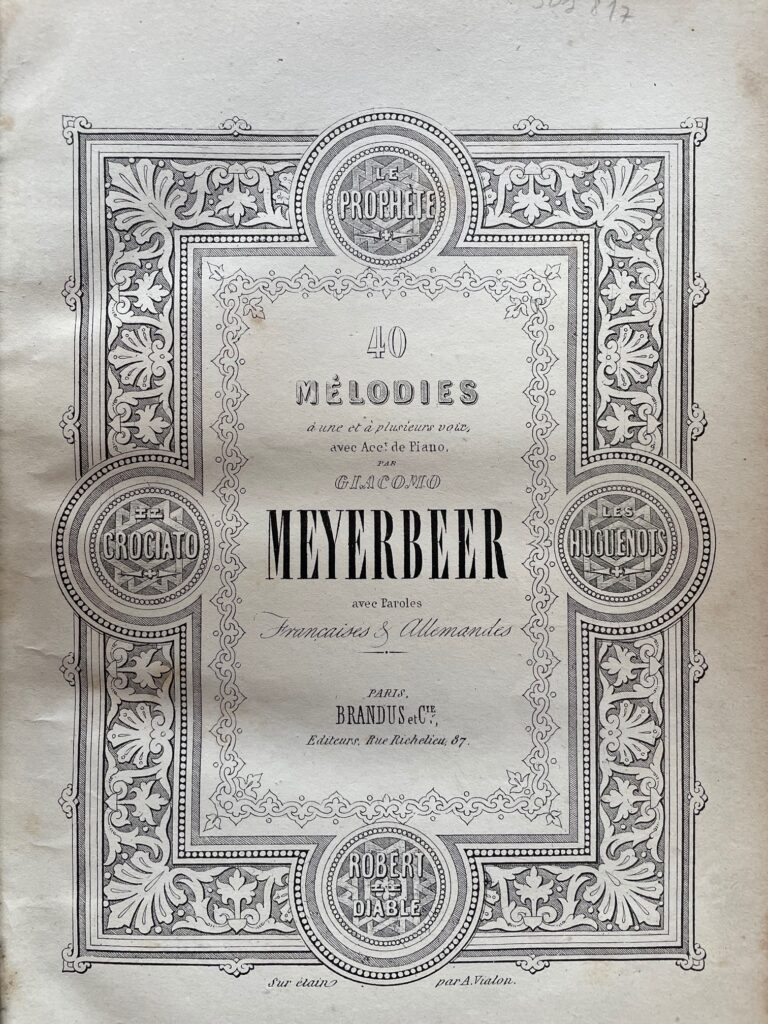

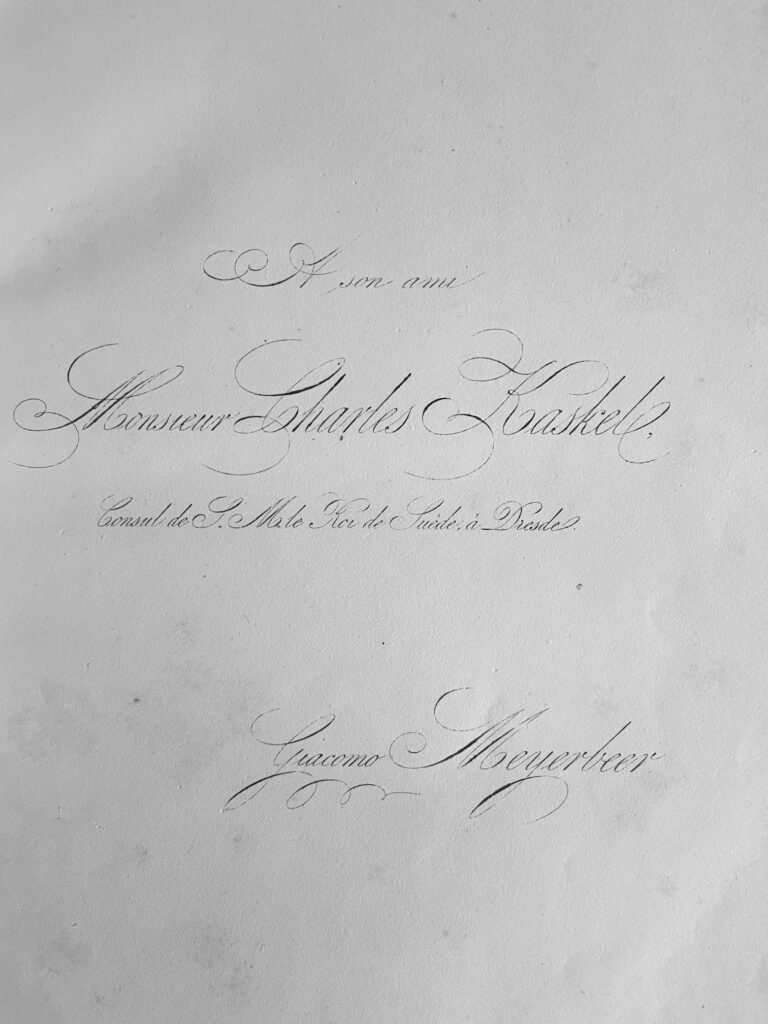

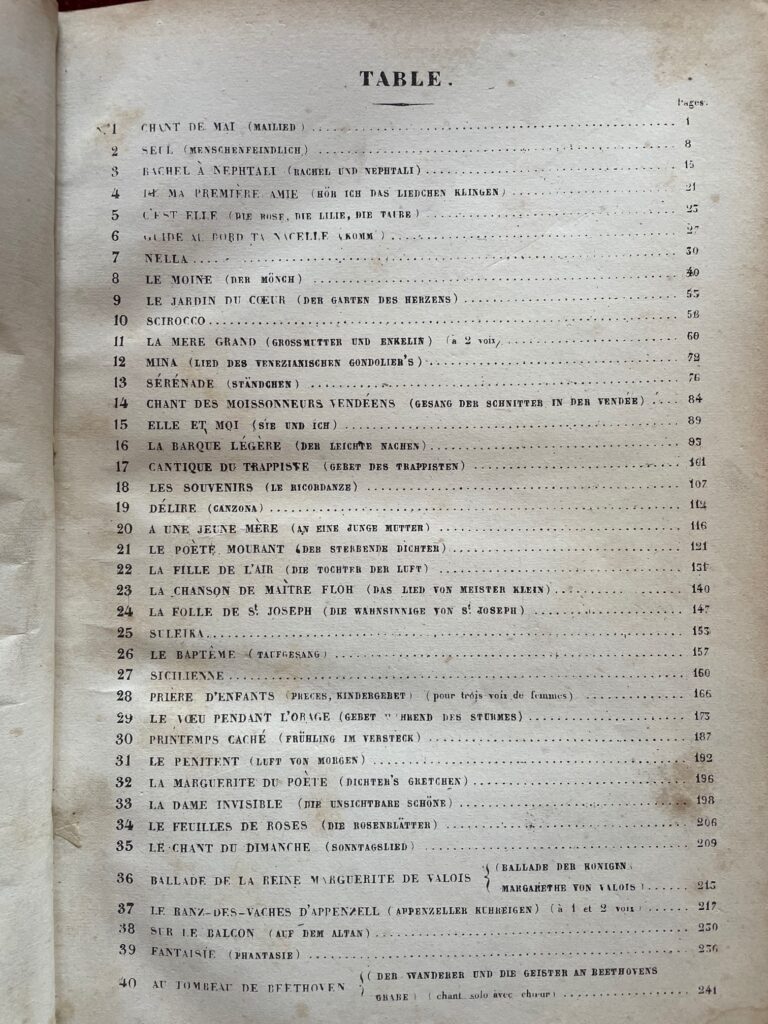

April 1850

The 40 Mélodies with German and French texts are published in Paris. Meyerbeer compiles the selection of songs himself and dedicates the edition to his long-time friend Karl von Kaskel (1797-1874). Kaskel was co-founder of the Dresdner Bank.

3 and 9 September 1850

The Neue Zeitschrift für Musik publishes the disgusting pamphlet Das Judenthum in der Musik (Judaism in music), written by a certain K. Freigedank: the Jews are not capable of any creative inspiration of their own, they can only imitate. At first, the essay attracted little attention. Nevertheless, 11 professors of the Leipzig Conservatory protest and demand the resignation of the journal’s editor, Franz Brendel. The thought worlds of the arsonist K. Freigedank still have an effect today.

1849/1850/1851

Performances of The Prophet in Paris, London, Marseille, Amsterdam, Hague, Hamburg, Dresden, Vienna, Frankfurt a. M., Schwerin, Leipzig, Darmstadt, Antwerp, Düsseldorf, Cologne, Sondershausen, Lisbon, Berlin, Graz, New 0rleans, Brunswick, Pest, Rostock, Aachen, New York, Hanover, Brussels, Bremen, Ulm, Greifswald, Breslau, Munich, Coburg, Augsburg, Basel, Göttingen, Liegnitz, Königsberg, Ghent, Würzburg, Prague, Mainz, Ballenstädt, Glogau, Gotha, Dessau, Lüneburg, Linz, Wiesbaden, Gdansk, Toulouse, Elbing, Nancy, Besancon, Mulhouse, Zurich, Baden-Baden, Constantinople, Brno, Bordeaux, Lyon, Lille, Strasbourg, Stuttgart, Mannheim, Bromberg, Colmar, Szczecin. Meyerbeer is an European celebrity.

May 31, 1851

On the occasion of the dedication of the monument to Frederick the Great by Christian Daniel Rauch (1777-1857), the Ode an Rauch (Ode to Rauch) is premiered. The text is written by August Kopisch (1799-1853).

August 1851

Meyerbeer becomes a member of the Berlin Academy of Arts.

May 8, 1853

In the presence of the Royal Family and the Belgian King Leopold I. First performance of the 91st Psalm a cappella for two choirs and solos in the Friedenskirche in Sanssouci Park, a commission from Frederick William IV. for the cathedral choir.

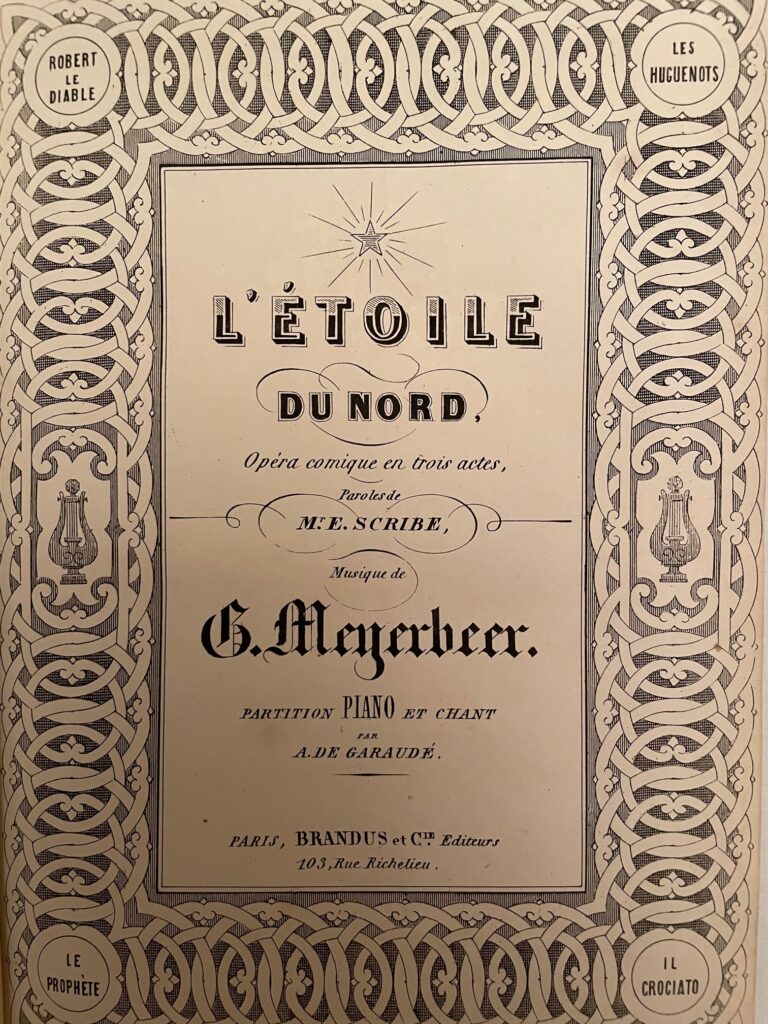

February 16, 1854

The opéra comique L’Étoile du Nord (The Northern Star) is successfully premiered in Paris. The music is partly from the Feldlager (camp). The libretto is written by Eugène Scribe.

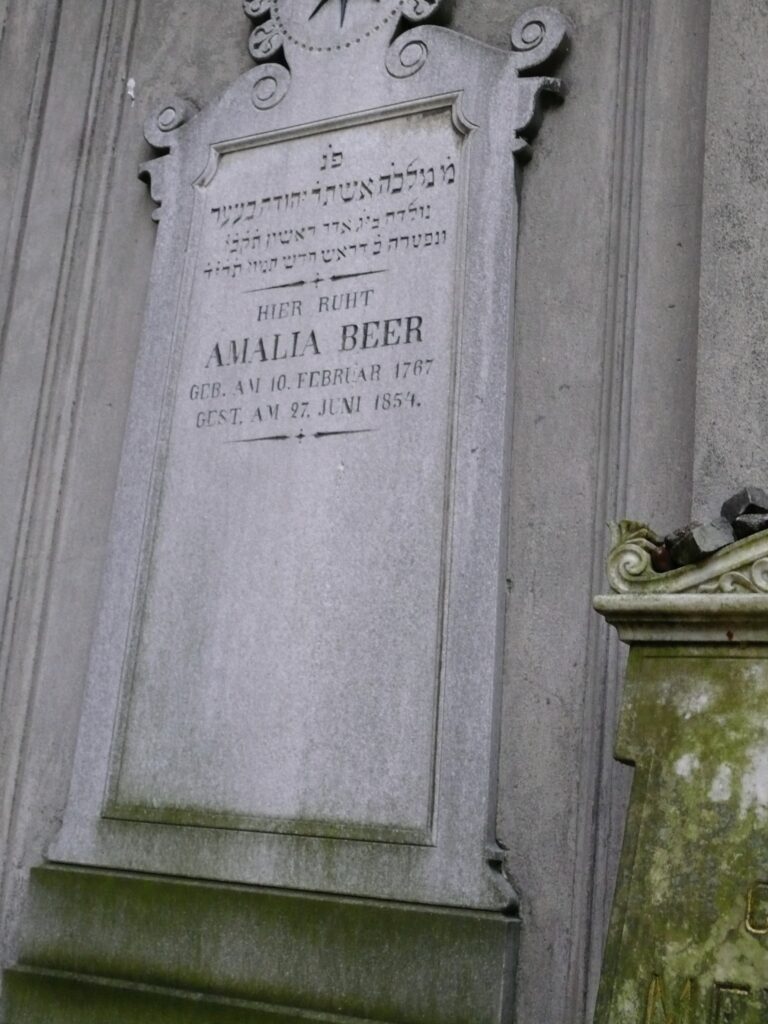

June 27, 1854

Amalie Beer, Meyerbeers beloved mother dies in Berlin.

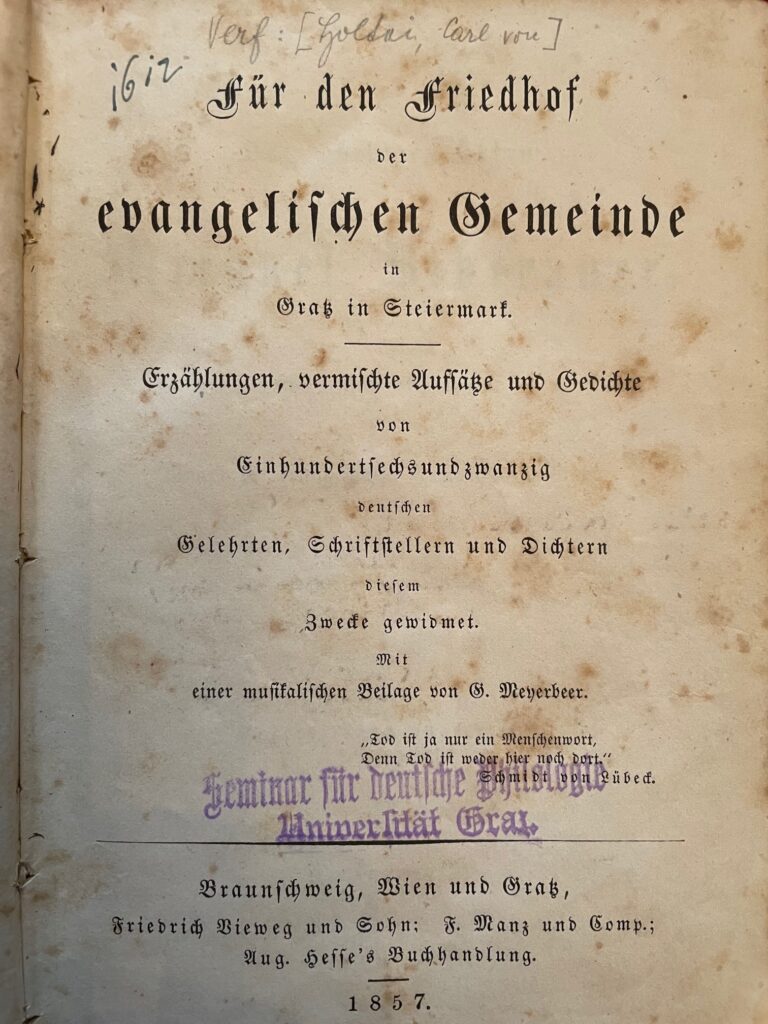

March 1857

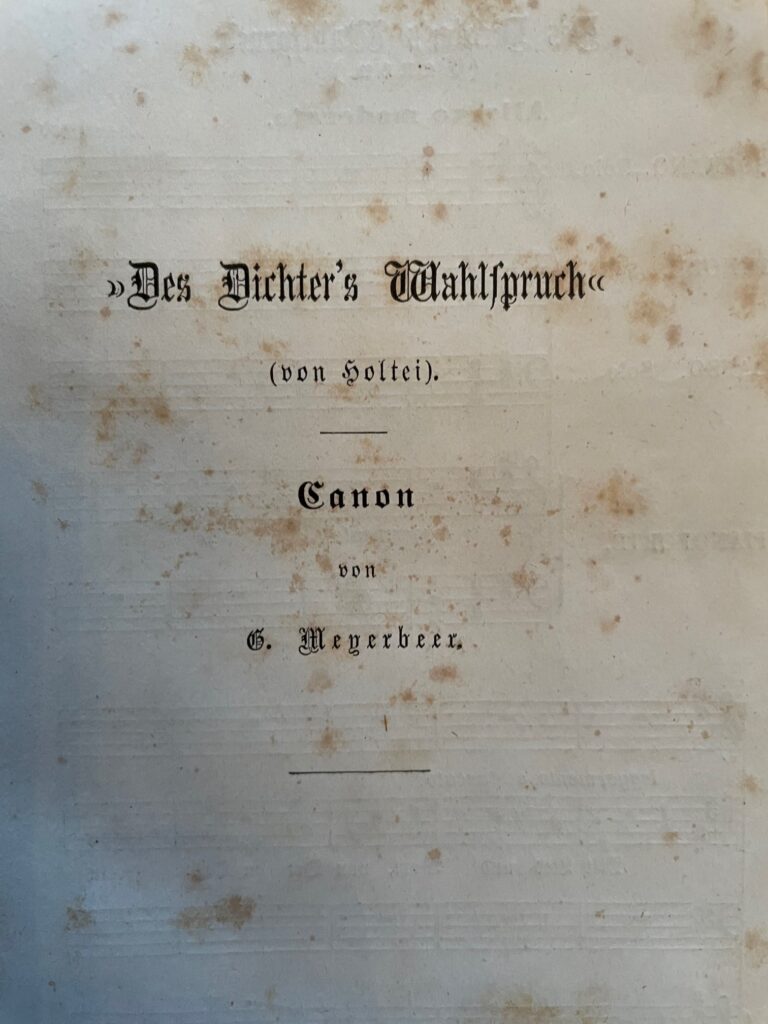

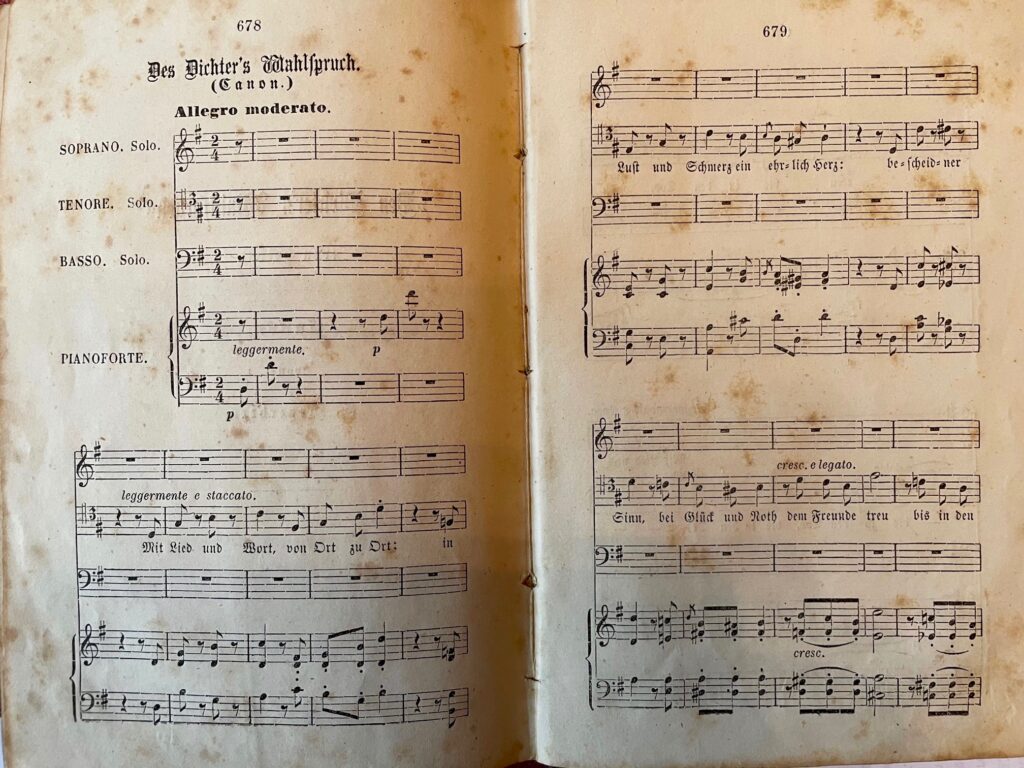

Karl von Holtei (1798-1880), a long-time friend of Beer and Meyerbeer, becomes involved with the Protestant cemetery in Graz in Styria. Meyerbeer contributes a canon to a text by Holtei for this charitable project.

April 4, 1859

First performance of the opéra comique Dinorah ou Le Pardon de Ploërmel (Dinorah or The Pardon of Ploërmel) in Paris. The libretto is written by Jules Barbier (1825-1901) and Michel Carré (1821-1871).

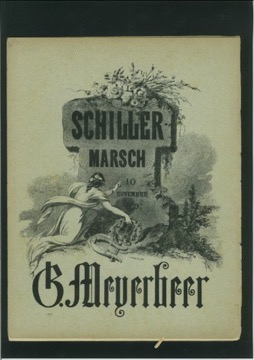

November 10, 1859

Great celebrations on the occasion of the 100th birthday of Friedrich von Schiller in the Cirque des Champs Elysées in Paris, organised by the German exile community. Meyerbeer composes for the occasion a Festmarsch (festive march) for orchestra and the festive song Wohl bist du uns geboren (you are well born to us) for orchestra choir and solos, the text is by Ludwig Pfau (1821-1894), who is living as a political émigré in France at the time.

February 21, 1861

Coronation of Wilhelm I. in Königsberg. Meyerbeers composes a Krönungsmarsch (coronation march) for the occasion. For health reasons he does not take part in the festivities.

April 20, 1862

Last journey to London, where the Great World’s Fair takes place. Meyerbeer composes an overture for the official opening on 1 May 1862.

May 2, 1864

Meyerbeer dies in Paris. On 6 May a moving funeral service takes place in the great hall in the Gard du Nord. Rossini composes the sentimental choral movement Quelques Mesures Funèbres à mon pauvre ami Giacomo Meyerbeer (Some Funeral Measures to my poor friend Giacomo Meyerbeer). The body is then transported to Berlin on a special train. Queen Augusta joins the train at the border station in Aachen and accompanies the coffin to Berlin. Meyerbeer stipulated in his will that he be buried in Berlin. On 9 May, he is buried in the family grave at the Jewish Cemetery on Schönhauser Allee with great public participation.

April 28, 1865

Posthumous premiere of the Grand Opéra Vasca de Gama under the title L’Africaine (The African) in Paris.

1869

Das Judenthum in der Musik (Judaism in music) is published as a separate pamphlet and with a preface. K. Freigedank reveals his identity. Richard Wagner hides behind the pseudonym. The publication sparks a controversial discussion.

Meyerbeer’s works are an integral part of all renowned opera houses until well after 1918.

1933-1945

No music by Meyerbeer is heard in Nazi Germany. Hate tirades are written about him. Hideous climax: Karl Blessinger: Judentum und Musik. Ein Beitrag zur Kultur- und Rassenpolitik. (Judaism in music. A Contribution to Cultural and Racial Politics) (1944).

1941

In his will, Meyerbeer established the Meyerbeer Foundation, from which a number of prizewinners emerged. The foundation became part of the Reich administration in 1938 and was dissolved in 1941 or 1942 in favour of the Reich, i.e. „aryanised“.

1958

After the devastating period between 1933-1945, a serious study of Meyerbeer’s life and work is finally possible. Although the embargo on the evaluation of the estate expires in 1932, by then it is known to be too late. It is thanks to the great Meyerbeer researcher Heinz Becker that the biased judgements against Meyerbeer’s music were stopped. Becker’s publication Der Fall Heine-Meyerbeer. Neue Dokumente revidieren ein Geschichtsurteil (The Heine-Meyerbeer Case. New documents revise a historical judgement) made it possible for the first time to take an objective look at Meyerbeer. A milestone in the reception of Meyerbeer.

1960

The first volume of Briefwechsel und Tagebücher Giacomo Meyerbeers (Giacomo Meyerbeer’s correspondence and diaries) is published under the direction of Heinz Becker. From the fifth volume onwards, Sabine Henze-Döhring takes over this mammoth task. The eighth and, for the time being, last volume, which covers the last years of Meyerbeer’s life, will be published in 2006. Anyone who is concerned with the cultural history of the 19th century cannot really avoid this edition. The correspondence and diaries provide a vivid testimony to his epoch-making impact.

To be continued!